Recently I visited the Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel exhibition at the Versa Studios in Leeds, one of its final venues on a world tour that was being staged by Special Entertainment Event, Inc.

From the outside, the studios looked like a nondescript modern office block, but when I stepped inside, from the dull gloom of modern Leeds, it was as if I had entered an entirely different realm of existence, glowing with the creative excellence of 34 gigantic reproductions of the frescos that Michelangelo painted in Rome’s Sistine Chapel in the early 16th Century – a work that still remains almost overwhelming in its timeless, transcendent grandeur.

If we regard Michelangelo’s frescos on the ceiling and altar wall of the Sistine Chapel as one large, single work, then there is a strong case for saying it’s the greatest painting in all of western art. Nothing else comes close to it for its inventive breadth and humanitarian depth of meaning. It is truly one of the wonders of the world.

One of the problems with visiting the actual Sistine Chapel in Rome – which attracts more than 5 million visitors each year – is that the ceiling is over sixty feet above the viewers’ heads, but here, in Leeds, one was able look at each life-size panel from just a few feet away. Every brush stroke, every blemish, and the full richness of every colour, could be seen exactly as Michelangelo first created it by brushing the paint directly into wet plaster.

Michelangelo in person

Even in his own lifetime (1475 – 1564), Michelangelo Buonarroti was so famous that he was known all the world over simply by his first name, derived from Archangel Michael, which was appropriate, for he soon acquired the nickname of Il Divino (“the Divine One”).

As a person, however, he was a melancholy introvert, a bizzarro e fantastico, a man who “withdrew himself from the company of men.” A contemporary, Condivi, said he was indifferent to food and drink, eating “more out of necessity than of pleasure”, and “often slept in his clothes and boots.” And the biographer Paolo Giovio describes him as “so rough and uncouth that his domestic habits were incredibly squalid.” In this respect he is reminiscent of another all-time artistic genius, the scruffy and misanthropic Ludwig van Beethoven. But, above all, Michelangelo’s contemporaries admired him for what they called his terribilità — his ability to instil a sense of awe in the viewers of his art.

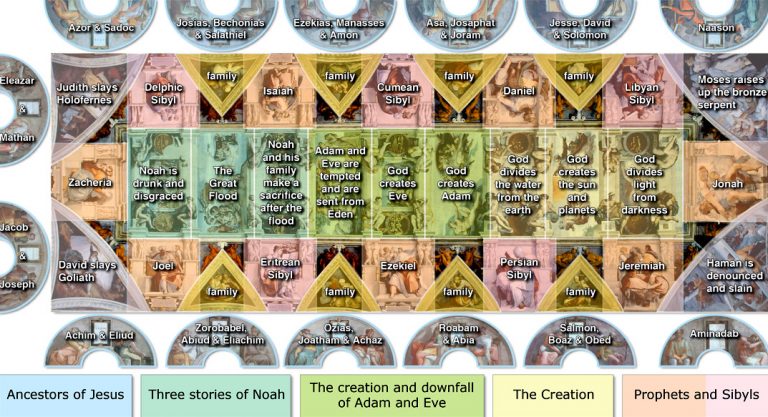

The frescos of the Sistine Chapel ceiling

The Sistine Chapel ceiling, which took Michelangelo four and a half years to paint (between 1508 and 1512), measures 128 by 45 feet, and consists of 39 separate paintings. (It seems that the number 39 may have been deliberate for numerologists called it ‘The Angel Number’, having the divisors of 1, 3, and 13 .)

The Pope needed to keep the Chapel in use while Michelangelo was painting the ceiling, so, when no one could supply suitable scaffolding, Michelangelo invented a method whereby planks were supported on brackets inserted into holes that he drilled into the side walls.

We need here to dismiss the myth that Michelangelo painted the ceiling lying on his back, as depicted by Charlton Heston in the 1965 film The Agony and the Ecstasy.

Vasari tells us that he painted all the frescos in a standing position, with his head tilted backwards.

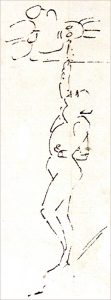

Michelangelo himself described it in a poem:

My beard turns up to heaven; my nape falls in,

Fixed on my spine: my breast-bone visibly

Grows like a harp: a rich embroidery

Bedews my face from brush-drops thick and thin.

And he drew his own accompanying sketch:

He proceeded from east to west, starting from the entrance of the Chapel to finish above the altar with a panel depicting God separating light from darkness.

The Creation of Adam

The most famous image in the ceiling paintings – perhaps the most famous in the whole history of art – is “The Creation of Adam” in which Adam and God reach out to each other with pointed fingers that don’t quite meet. Here Michelangelo is expressing his new-found spiritual belief, influenced by the Reformation, that man could communicate with God directly through the intellect. With the added implication that the Church itself could be bypassed.

Nevertheless, when Michelangelo eventually finished the ceiling frescos at the age of 37, the pope liked it and staged a grand unveiling ceremony at which, in Vasari’s words, everyone was left “amazed and speechless”.

The Last Judgement

Some 25 years later, in 1533, Pope Clement VII, who as Condivi said, “thought of one thing after another … resolved to have the Day of the Last Judgement painted” on the altar wall. Michelangelo “tried as best he could to avoid this new commission,” but when Pope Clement died suddenly, the new Pope, Paul III, determined to proceed with it, and appointed him now as the official sculptor, painter, and architect for the Vatican. So, after making various cartoons, Michelangelo decided on creating one homeogenous composition that would cover the entire 2000 square-foot wall. This required rebuilding the wall with specially baked bricks and then erecting scaffolding. The huge fresco – which was inspired strongly by Dante’s Divine Comedy, written 200 years earlier – took the ageing Michelangelo over four years to complete, before being unveiled on All-Hallows Eve 1541, exactly 29 years after he’d completed the ceiling fresco.

It is an extraordinarily well-planned composition, like a gigantic relief, of 139 massive sculptural figures of the saints (the number 39 again), with those on the left rising to heaven and those on the right descending to hell around the central figure of Christ.

Intriguing amongst these is Saint Bartholomew, who is holding a drooping flayed skin bearing Michelangelo’s pained face.

Some claim Michelangelo was referring here to his own ‘martyrdom’ involved in the labour of making the painting, but a more likely explanation was that he had been experiencing an agonising split with Christian orthodoxy in that his personal beliefs still retained elements pagan Humanism. To which extent he regarded himself as a sinner, not worthy of the Catholic church. When he was dying he said, “I regret that I have not done enough for the salvation of my soul.” Today he is best regarded as belonging to a school of “Christian Humanists”.

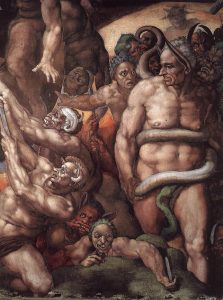

Another interesting detail was the result of a preview visit made by the Pope’s Master of Ceremonies, Biagio da Cesena, before the work was completed. Cesena complained that it was “disgraceful that in so sacred a place there should have been depicted all those nude figures, exposing themselves so shamefully, and that it was no work for a papal chapel but rather for the public baths and taverns.”

In revenge for this comment Michelangelo immediately put the face of Cesena on Minos in Hell, in the bottom right-hand corner, complete with donkey ears, and with his nudity covered by a coiled snake.

When Cesena complained to the pope, the pontiff joked that his jurisdiction did not extend to Hell, so the portrait would have to remain.

On completion of the Last Judgement in 1541, Michelangelo was nearly 67. Again, the pope, this time Paul III, was so impressed at its unveiling that he fell to his knees exclaiming “Lord, charge me not with my sins on the Day of Judgement”. And Vasari said “in it may be seen marvellously portrayed all the emotions that mankind can experience.”

Criticism of The Last Judgement

But soon – although the Bible says clearly that on Judgment Day we will all stand naked before the Redeemer – the Cardinals were complaining that the nudity of Christ and the Virgin Mary was sacrilegious. So, shortly before Michelangelo’s death in 1564, one of his apprentices, Daniele da Volterra, was commissioned to obscure the genitals.

For three centuries after Michelangelo completed the fresco, a steady stream of “improvers” was employed by various Popes to hack out the nudes’ genitals or obscure them with fig leaves. Overall, 38 nudes were censored – on might say disfigured – in this way.

20th Century restoration of the frescos

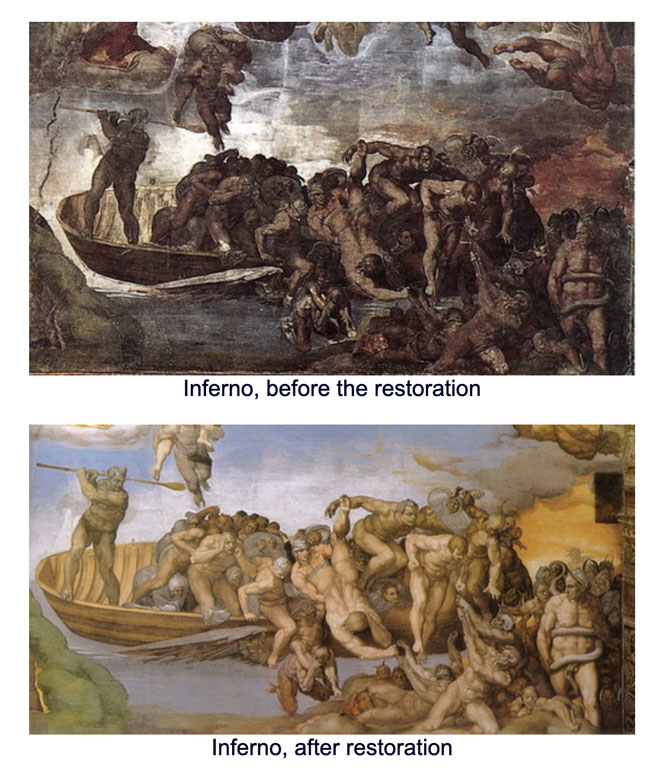

Over the centuries, the Sistine Chapel frescos became so soiled by “layers of unsaturated fat from five hundred years’ worth of candles and oil lamps, together with thick layers of glue and linseed-oil varnishes slathered across the fresco during multiple incompetent restorations” (Ross King p.123) that by the 1980s cleaning and restoration had become essential. This involved first making repairs to the plaster before removing the grime with special solvents. Then, where necessary, retouching was carried out using water colours (though some areas were deliberately left unrestored as a historical record). Finally, a “light layer of acrylic” was applied to protect the surface.

Unfortunately, one change the restorers were unable to make was the removal of the various loincloths and flying robes that had been added to the composition to cover the genitals of the saints and sinners.

Amazingly, a number of art critics did not like the restoration. They argued absurdly that the traditional murky gloom of the frescos was somehow part of the work of art. Richard Serrin, for example, went so far as to say that it had “destroyed them forever.” But Carlo Pietrangeli, Director General of the Vatican Museums at the time, described it as being “like opening a window in a dark room and seeing it flooded with light.”

Which chimes nicely with the words of the painter, architect and historian, Giorgio Vasari (1511-74), who called the Sistine Chapel ceiling “a veritable beacon for our art … restoring light to a world that for centuries had been plunged into darkness.”

A final word: Michelangelo’s work ethic

Michelangelo’s work is glowing reminder of what can be achieved by a single human being who has sufficient imagination, craftsmanship, care and application, even if his level of genius was exceptional. He, however always emphasised his sheer hard work. Just as Johann Sebastian Bach asserted that “Anyone who works as hard as I did will be equally successful”, so Michelangelo said “if people knew how hard I worked to get my mastery, it wouldn’t seem so wonderful at all.” And he added that “there is no greater harm than that of time wasted.” (This is a precept I have tried to follow, not always with success, in my own creative life.)

The idea of his ever easing up was unthinkable, and he carried on producing further major works of art, sculpture and architecture (various major palaces, chapels and tombs) in what he called his “second childhood”. And when he was on his deathbed in 1564 (at the then-considerable age of 88 – the average age of death being about 40), he muttered; “I’m still learning.”

As a modern commentator has rightly commented, we are all still learning.

Please also see gallery of pictures below

Select bibliography

Luciano Berti, All the Works of Michelangelo, trans. by Susan Glasspool, Bonechi Editori, Firenze, 1968.

Ross King, Michelangelo & the Pope’s Ceiling, Walker Publishing, 2002.

Howard Hibbard, Michelangelo, (2nd Edition), Penguin Books, 1985.

Further details about Michelangelo’s “Christian Humanism” may be found in the excellent article on Michelangelo in the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel: The Exhibition: Discovery, Inspiration, Reflection. (Curiously, there is a second website that does more or less exactly the same job.) Sadly, although it is still scheduled to visit at least 20 more venues world-wide, there will be no more planned in Britain, having been to Glasgow, Halifax, Birmingham, Manchester and London.

STOP PRESS. Owing to popular demand the exhibition has now been extended until November 20th.

Selected photos I took of the exhibition